반응형

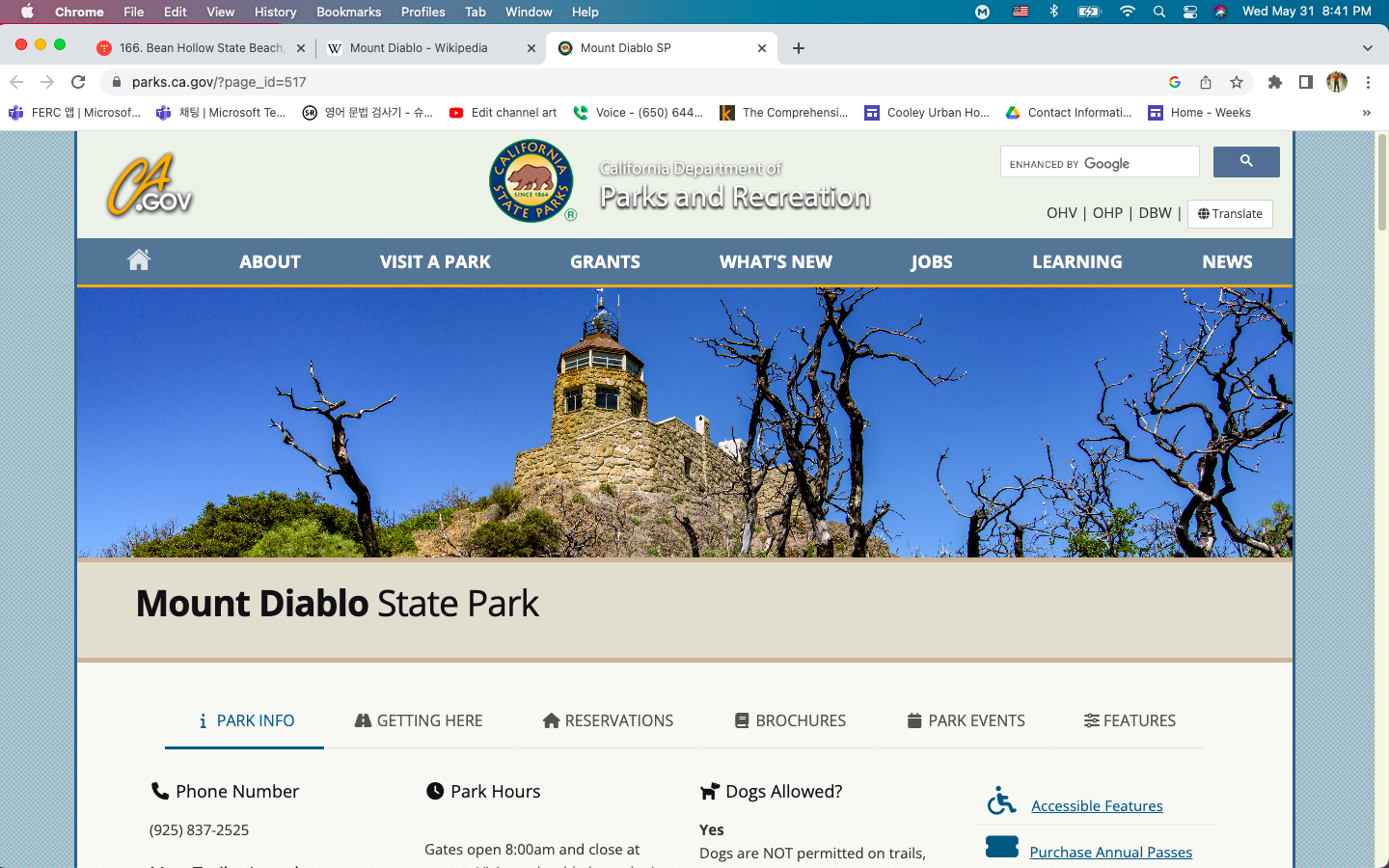

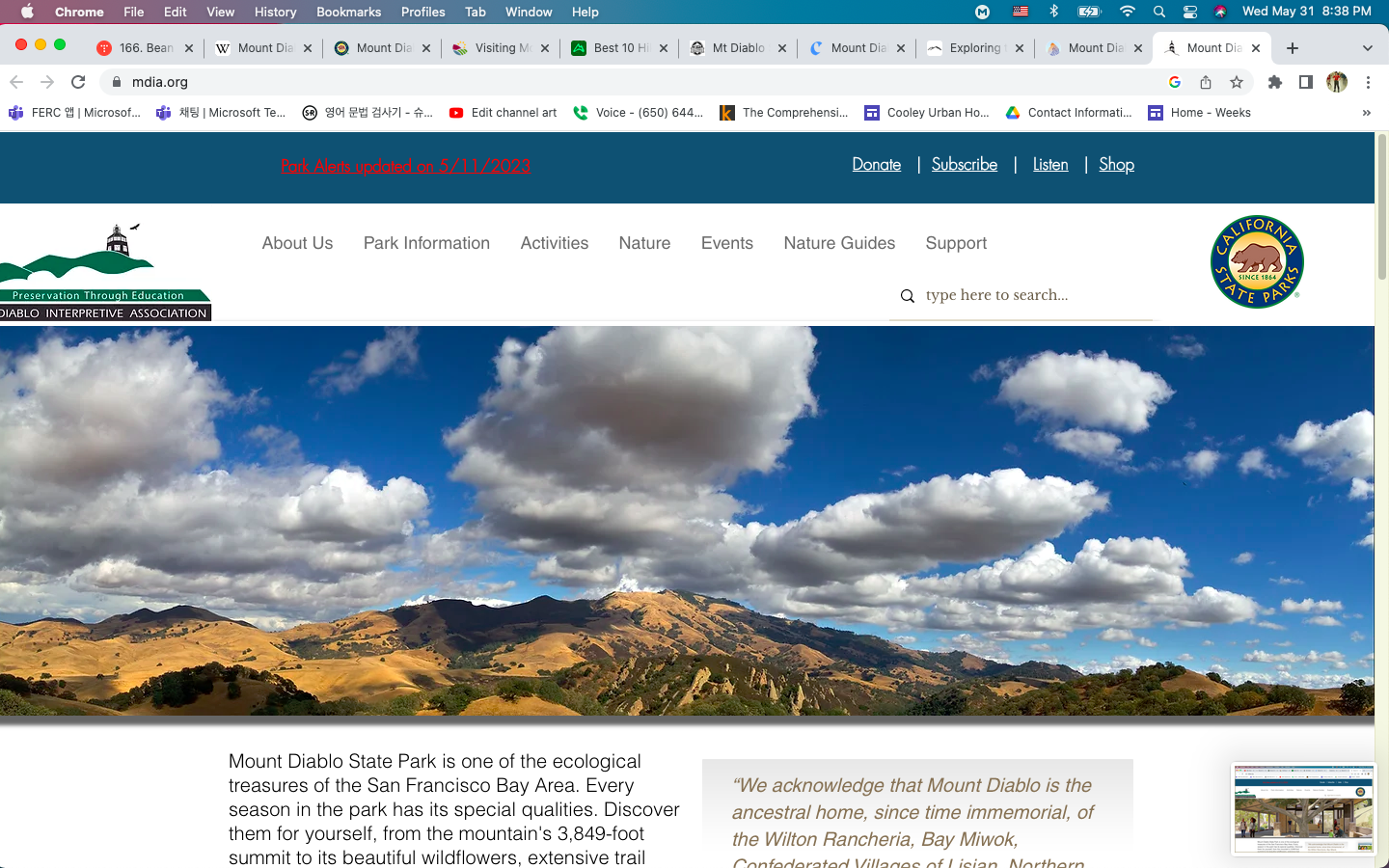

Mount Diablo is a mountain of the Diablo Range, in Contra Costa County of the eastern San Francisco Bay Area in Northern California. It is south of Clayton and northeast of Danville. It is an isolated upthrust peak of 3,849 feet (1,173 meters), visible from most of the San Francisco Bay Area. Mount Diablo appears from many angles to be a double pyramid and has many subsidiary peaks. The largest and closest is North Peak, the other half of the double pyramid, which is nearly as high in elevation at 3,557 feet (1,084 m), and is about one mile (1.6 kilometers) northeast of the main summit. The mountain is within the boundaries of Mount Diablo State Park, which is administered by California State Parks.

.

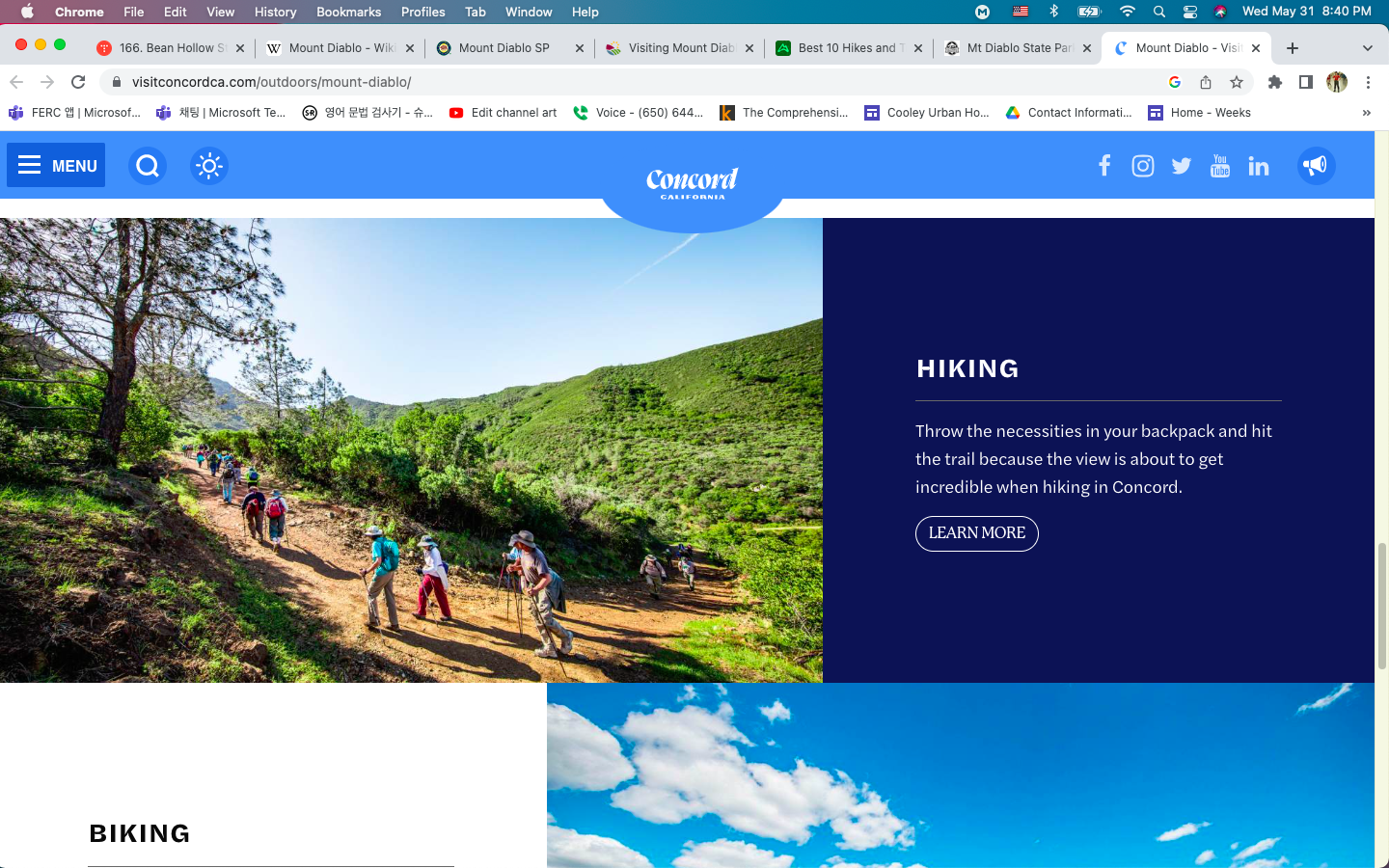

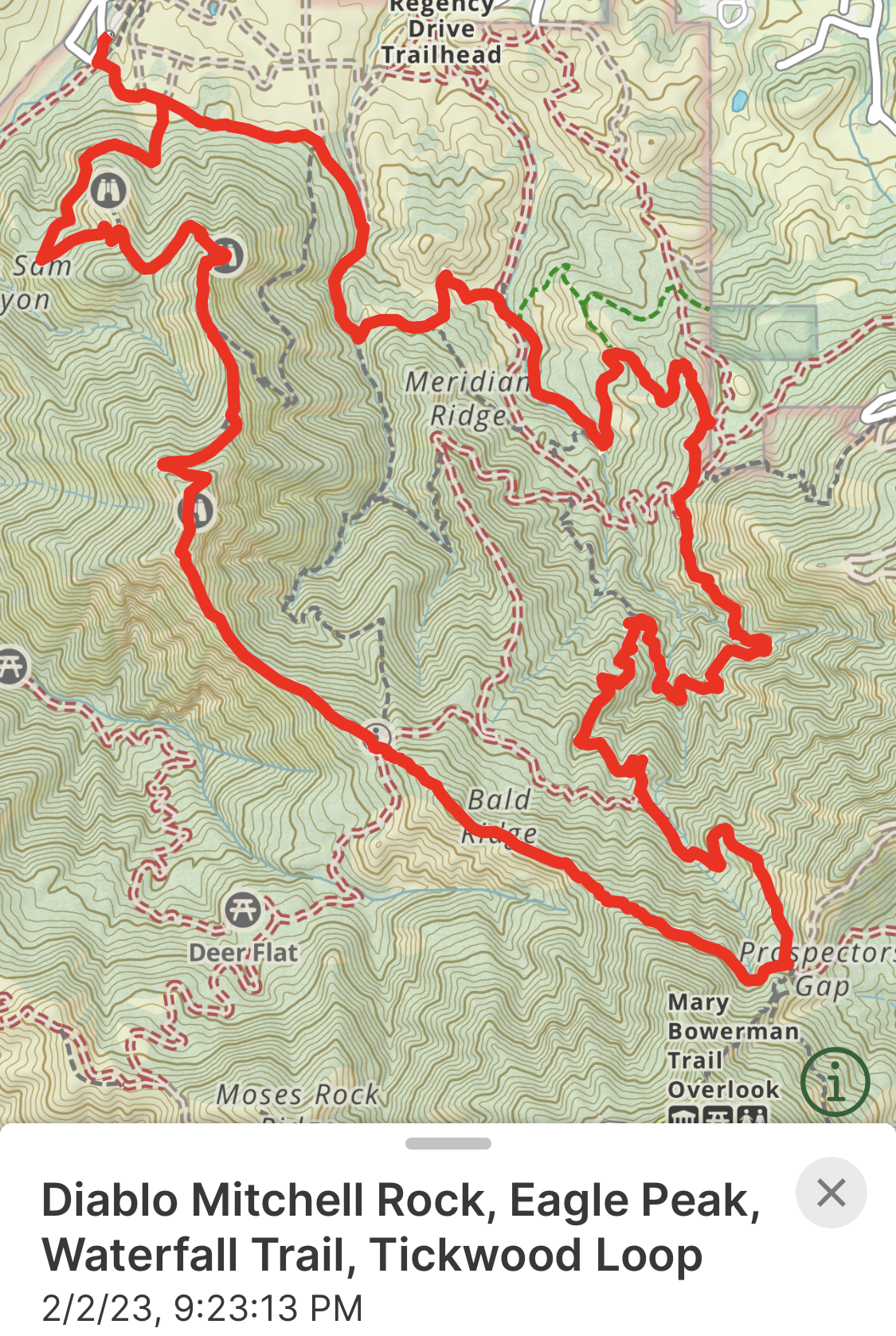

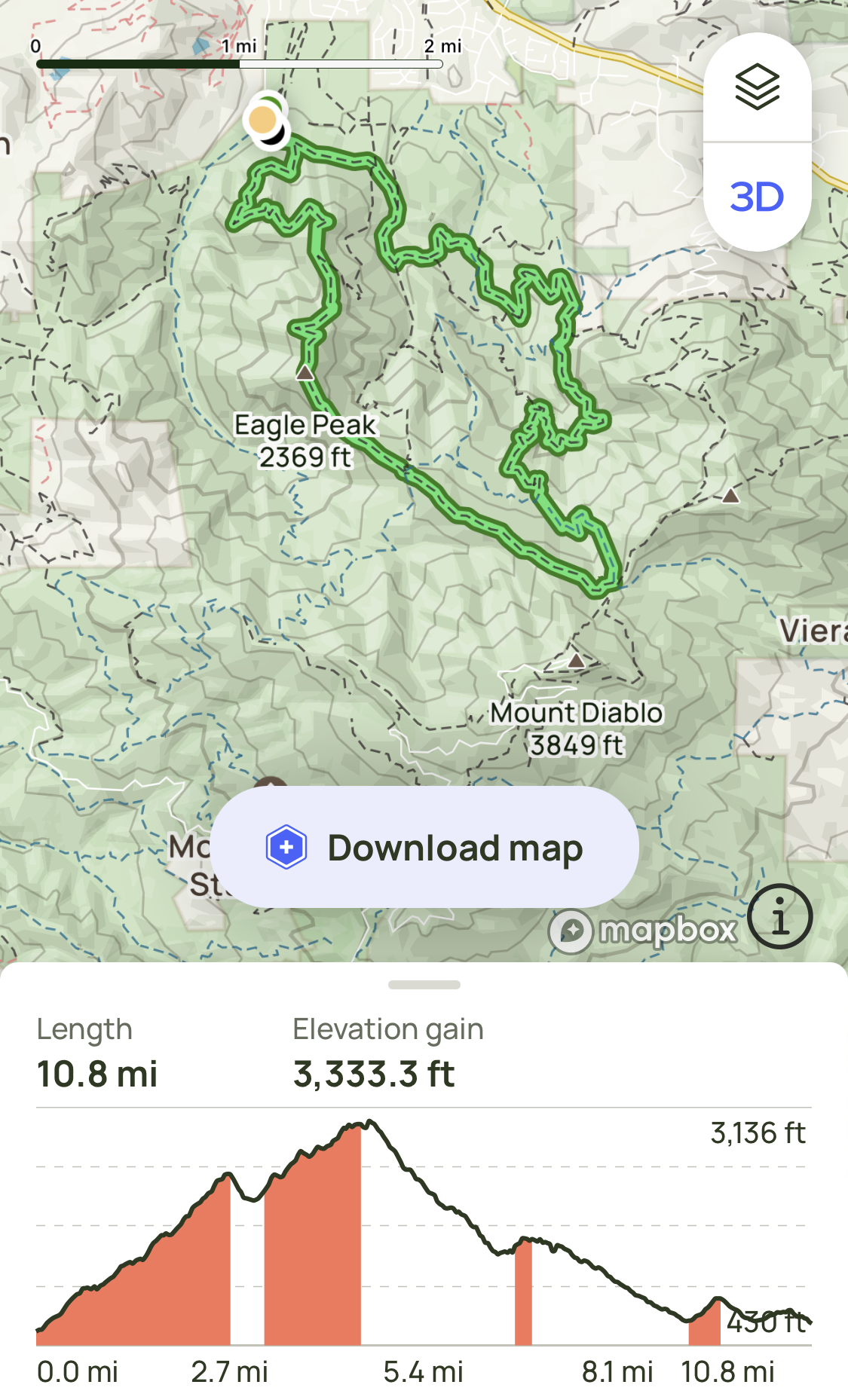

The summit is accessible by foot, bicycle, or motor vehicle. Road access is via North Gate Road or South Gate Road. Also you can hike in various places in Mount Diablo. The peak is in Mount Diablo State Park, a state park of about 20,000 acres (8,000 hectares). The state park was the first public open space established on or near the peak. According to the non-profit Save Mount Diablo, there are now varied types of protected lands on and around Mount Diablo that total more than 90,000 acres (36,000 ha). These include 38 preserves, such as nearby city open spaces, regional parks, and watersheds, which are buffered in some areas with private lands that have been protected by conservation easements. The day use fee per vehicle for the park varies according to the entrance: $6 via Macedo Ranch (Alamo) or Mitchell Canyon (Clayton), and $10 via South Gate Rd. (Danville) & North Gate Rd. (Walnut Creek) leading up Mount Diablo.

.

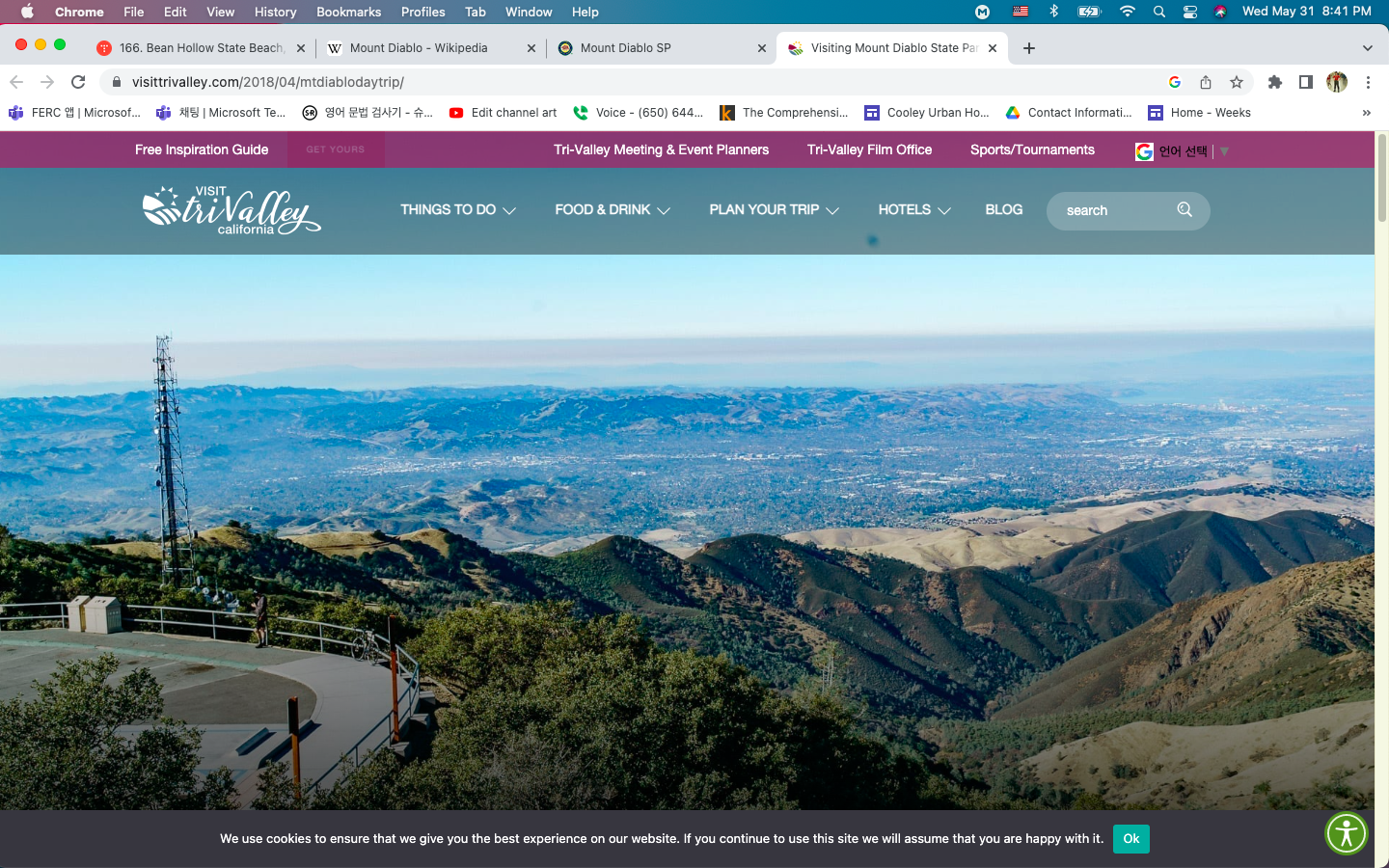

On a clear day, the Sierra Nevada range is plainly visible from the summit. The best views are after a winter storm; a snowy Sierra shows up better, and summer days are likely to be hazy. Lassen Peak, 181 miles (291 kilometers) away, is occasionally just visible over the curve of the earth. Sentinel Dome in Yosemite National Park is visible, but Half Dome is hidden by the 8000-foot ridge at 37.755N 119.6657W. Eight bridges are visible, from left to right (southwest to northeast): San Mateo, Bay, Golden Gate, San Rafael, Carquinez, Benicia, Antioch, and Rio Vista. Claims that the mountain's viewshed is the largest in the world—or second largest after Mount Kilimanjaro—are ill-founded. It does boast one of the largest viewsheds in the Western United States and played a key role in California history. Countless peaks in the state are taller, but Mount Diablo has a remarkable visual prominence for a mountain of such low elevation. Its looming presence over much of the Bay Area, delta, and Central Valley, and good visibility even from the Mother Lode, all key regions during the gold rush and early statehood, made it an important landmark for mapping and navigation. The summit is used as the reference datum for land surveying in much of northern California and Nevada.

.

Mount Diablo is sacred to many California Native American peoples. According to Miwok mythology and Ohlone mythology, it was the point of creation. The local peoples of the area traditionally had a variety of creation narratives associated with the mountain. In one surviving narrative fragment, Mount Diablo and Reed's Peak (Mount Tamalpais) were surrounded by water; from these two islands the creator Coyote and his assistant Eagle-man made Native American people and the world. In another, Molok the Condor brought forth his grandson Wek-Wek the Falcon Hero, from within the mountain. About 25 independent tribal groups with well-defined territories lived in the East Bay countryside surrounding the mountain. Their members spoke dialects of three distinct languages: Ohlone, Bay Miwok, and Northern Valley Yokuts. The Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone from Mission San Jose and the East Bay area, called the mountain Tuyshtak, meaning "at the dawn of time". Further inland, the Nisenan of the Sacramento Valley called it Sukkú Jaman, "dog mountain"; because, as Nisenan elder Dalbert Castro once explained, it's "the place where dogs came from in trade". A Southern Sierra Miwok name for the mountain was Supemenenu, and a Northern Sierra Miwok name was Oj·ompil·e.

.

It has also been suggested that another early Native American name for the mountain was Kawukum or Kahwookum, but there is no evidence to confirm the assertion. According to Indian historian Bev Ortiz and Save Mount Diablo: "The name Kahwookum was made up in 1866 — with no real Native American connection — referred to the California Legislature's Committee on Public Morals, and tabled. It resurfaced as a real estate gimmick in 1916 with a supposed new translation, "Laughing Mountain", attributed without documentation to Diablo area Volvon Indians. Most of Mount Diablo, including its peak, was within the homeland of the early Volvon (sometimes spelled Wolwon, Bolbon or Bolgon), a Bay Miwok–speaking tribe. As early as 1811, Spanish colonists referred to the mountain as Cerro Alto de los Bolbones ("High Hill of the Volvon") or sometimes Sierra de los Bolgones. This name persisted for awhile but was replaced in 1850 by the Americans.

.

The conventional view is that the peak derives its name from the reaction of Spanish soldiers to the 1805 escape of several Chupcan Native Americans in a willow thicket some 7 miles north of the mountain. One story tells that their nighttime escape through the thicket was aided by mysterious lights. An 1850 report by General Mariano G. Vallejo tells of a strange dancing spirit turning the battle in favor of the Chupcan. Vallejo interpreted the natives' word for the personage, puy, to mean "devil" in the Anglo-American language. Vallejo's report could be interpreted to align with Edward G. Gudde's history of place names. (Kyle, and Ortiz)

.

By 1824, the region north of the mountain came to be known as Monte del Diablo ("devil's thicket"; in this case monte should be translated as thicket or dense woods). It was shown on maps near present-day Concord (formerly known as Pacheco). Later, U.S. settlers understood "Monte" to refer directly to the mountain, and it was recorded with varying degrees of certainty until "Mount Diablo" became official in 1850. In May 1862, California Geological Survey field director William H. Brewer named the northeast peak of Mount Diablo "Mount King," after Rev. Thomas Starr King, a Unitarian clergyman, abolitionist, Republican, Yosemite advocate, cultural Unionist, and California's leading intellectual. Today it is known simply as North Peak.

.

In 2005 Arthur Mijares, from the neighboring town of Oakley, petitioned the federal government to change the name of the mountain, claiming it offended his Christian beliefs. Additionally, he claimed that Diablo is a living person, and so is banned under federal law. He suggested renaming the mountain Mount Kawukum, and later, Mount Yahweh. Suggestions by other individuals included Mount Miwok and Mount Ohlone, after local Indian tribes. Finally Mijares proposed Mount Reagan, but the board rejected it on the grounds that a person must be deceased for five years to have a geographic landmark named after them. Eventually, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names rejected the petitions, saying there was no compelling reason to change the name.

.

In 2009 Mijares again proposed the name Mount Reagan to the United States Board of Geographic Names because the late president was by then eligible. The board gave the Contra Costa County Supervisor's Committee until March 31 to file an opinion. Individual members of the committee have responded that although they respect Reagan, Mount Reagan is not an appropriate name for the historic mountain. Later, the board unanimously voted against renaming the mountain, citing its historical significance.

.

In 1851 the south peak of the mountain was selected by Colonel Leander Ransom as the initial point—where the Mount Diablo Base and Mount Diablo Meridian lines intersect—for cadastral surveys of a large area. Subsequent surveys in much of California, Nevada and Oregon were located with reference to this point. Toll roads up the mountain were created in 1874 by Joseph Seavey Hall and William Camron (sometimes "Cameron"); Hall's Mount Diablo Summit Road was officially opened on May 2, 1874. Camron's "Green Valley" road opened later. Hall also built the 16-room Mountain House Hotel near the junction of the two roads, a mile below the summit (2,500 foot elevation. (It operated through the 1880s, was abandoned in 1895, and burned c. 1901). As far north as Meridian Road, on the outskirts of Chico, California, the summit was used as a reference point. The road is colinear with the summit, and is named for the meridian which intersects it. An aerial navigation beacon, the Standard Diablo tower, was erected by Standard Oil at the summit in 1928. The 10-million-candlepower beacon became known as the "Eye of Diablo" and was visible for a hundred miles.

.

After initial legislation in 1921, the state of California acquired enough land in 1931 to create a small state park around the peak. Many improvements were carried out in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps, but park expansion slowed in the 1940s through the 1960s. Significantly, botanist Mary Leolin Bowerman (1908–2005), founder of the Save Mount Diablo non-profit in 1971, published her Ph.D. dissertation in 1936 at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1944 she published her book, The Flowering Plants and Ferns of Mount Diablo, California. Her study boundaries became the basis for the state park's first map and for the park's eventual expansion. Her work also became the origin of many of the park's place names.

.

Mount Diablo was used for broadcasting purposes in the 1950s by radio station KSBR-FM and television station KOVR (channel 13). The Mount Diablo site gave KOVR, which was based in Stockton, regional coverage that also included San Francisco and Sacramento. However, it also forced the station to pay San Francisco rates for movies and impeded any attempt at obtaining network affiliation. In 1957, the station relocated to Butte Mountain in Jackson in order to become an ABC affiliate and remove its signal from the Bay Area. This state park has been greatly expanded over the decades. Soon after Earth Day in 1971, the nonprofit organization "Save Mount Diablo" was created by co-founders Mary Bowerman and Art Bonwell, barely ahead of real estate developers. At the time, the state park included just 6,788 acres (2,747 ha) and was the only park in the vicinity of the mountain. In 2007 the state park totaled almost 20,000 acres (8,100 ha), and with 38 parks and preserves on and around the mountain, Diablo's public lands total more than 90,000 acres (36,000 ha). According to Save Mount Diablo, there are 50 individual preserves on and around Mount Diablo, some of which are conservation easements covering a single parcel, others are expected to eventually be absorbed into larger nearby parks. As of December 2007, the organization recognizes 38 specific Diablo parks and preserves.

.

The State Park adjoins park lands of the East Bay Regional Park District, including Morgan Territory Regional Preserve, Brushy Peak Regional Preserve, Vasco Caves Regional Preserve, and Round Valley Regional Preserve. It also adjoins protected areas owned or controlled by local cities such as the Borges Ranch Historic Farm, the Concord Naval Weapons Station (now in the process of being converted to non military use), Indian Valley, Shell Ridge Open Space and Lime Ridge Open Spaces near city of Walnut Creek, and east to the Los Vaqueros Reservoir watershed. The new Marsh Creek State Park[a] and Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve are among the open spaces stretching to the north. In this way the open spaces controlled by cities, the East Bay Regional Park District, Mount Diablo State Park, and various regional preserves now adjoin and protect much of the elevated regions of the mountain. There are unprotected areas in Arroyo del Cerro, Curry Canyon, the Marsh creek region, and on the northern slopes of North Peak, and in a number of inholdings surrounded by preserve land.

.

Park expansion continues on all sides of the mountain although its western boundaries are largely complete. Extensive development continues in the southwestern foothills and Tassajara region, such as the upscale development of Blackhawk and individual estates overlooking the Livermore Valley on Morgan Territory Road. Other large projects are proposed in the northern Black Diamond Mines and Los Medanos foothills, at the Concord Naval Weapons Station, and near Cowell Ranch State Park. Large-scale development of other private parcels is restricted by city and county urban limit lines, by lack of water, excessive slope, and sensitive resources including rare species. Development of smaller ranchette subdivisions continue to fragment and threaten many parcels and large areas of habitat.

.

In 2007 Save Mount Diablo published Mount Diablo, Los Vaqueros & Surrounding Parks, Featuring the Diablo Trail, the most accurate and up-to-date map of Mount Diablo's more than 90,000 acres (36,000 ha) of protected lands. It includes 100 access points, 520 miles (840 km) of trail, and 400 miles (640 km) of private fire roads. Updated acreages and trail mileages were discussed in accompanying press materials and news articles.

.

Mount Diablo is a geologic anomaly about 30 miles (50 km) east of San Francisco. The mountain is the result of geologic compression and uplift caused by the movements of the Earth's plates. The mountain lies between converging earthquake faults and continues to grow slowly. While the principal faults in the region are of the strike-slip type, a significant thrust fault (with no surface trace) is found on the mountain's southwest flank. The uplift and subsequent weathering and erosion have exposed ancient oceanic Jurassic and Cretaceous age rocks that now form the summit. The mountain grows from three to five millimeters each year.

.

The upper portion of the mountain is made up of volcanic and sedimentary deposits of what once was one or more island arcs of the Farallon Plate dating back to the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, between 90 and 190 million years ago. During this time, the Farallon Plate was subducting beneath the North American continent. These deposits were scraped off the top and accreted onto the North American Plate. This resulted in the highly distorted and fractured basalt and serpentine of the Mount Diablo Ophiolite and metasediments of the Franciscan Complex around the summit. East of the subduction zone, a basin was filling with sediment from the ancestral Sierra further to the east. Up to 60,000 feet (18,000 m) of sandstone, mudstone, and limestone of the Great Valley Sequence were deposited from 66 to 150 million years ago. These deposits are now found faulted against the Ophiolite and Franciscan deposits.

.

Fossilized sea shells in the sandstone at the summit of Mt. Diablo (about 3,800' MSL) Over the past 20 million years continental deposits have been periodically laid down and subsequently jostled around by the newly formed San Andreas Fault system, forming the Coast Ranges. Within the last four million years, local faulting has resulted in compression, folding, buckling, and erosion, bringing the various formations into their current juxtaposition. This faulting action continues to change the shape of Mount Diablo, along with the rest of the Coast Ranges.

.

The summit area of Mount Diablo is made up of deposits of gray sandstone, graywacke, chert, oceanic volcanic basalts (greenstone) and a minor amount of shale. The hard red Franciscan chert is sedimentary in origin and rich in microscopic radiolaria fossils. In the western foothills of the mountain there are large deposits of younger sandstone rocks also rich in seashells, severely tilted and in places forming dramatic ridgelines. Mount Diablo forms a double pyramid which gives the appearance of a volcano although in fact it is formed of ancient sea floor rock being uplifted by relatively recent tectonic forces.

.

Deposits of glassmaking-grade sand and lower-quality coal north of the mountain were mined in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but are now open to visitors as the Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve. Guided tours of the sand mines and coal field are provided.

.

The park's vegetation is mixed oak woodland and savannah and open grassland with extensive areas of chaparral and a number of endemic plant species, such as the Mount Diablo manzanita (Arctostaphylos auriculata), Mount Diablo fairy-lantern (Calochortus pulchellus), chaparral bellflower (Campanula exigua), Mount Diablo bird's beak (Cordylanthus nidularius), and Mount Diablo sunflower (Helianthella castanea). The park includes substantial thickets, isolated examples, and mixed ground cover of western poison oak. (It is best to learn the characteristics of this shrub and its toxin before hiking on narrow trails through brush and to be aware that it can be bare of leaves (but toxic to contact) in the winter.)

.

At higher altitudes and on north slopes is the widely distributed foothill pine (Pinus sabiniana). Knobcone pine (Pinus attenuata) may be found along Knobcone Pine Road in the southern part of the park. The park and nearby Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve mark the northern extreme of the range of Coulter pine (Pinus coulteri). This species may be seen along the Coulter Pine Trail near the north (Mitchell Canyon) entrance.

In 2005 the endangered species Mount Diablo buckwheat (Eriogonum truncatum), thought to be extinct since last seen in 1936, was rediscovered in a remote area of the mountain.

This Pinus sabiniana (foothill pine), the most common tree species in the park, is dwarfed by harsh conditions near the summit of Mount Diablo.

This Pinus sabiniana (foothill pine), the most common tree species in the park, is dwarfed by harsh conditions near the summit of Mount Diablo.

All vegetation, minerals and wildlife within the park are protected and it is illegal to remove such items or to harass any wildlife.

Commonly seen animals include coyote, bobcat, black-tailed deer, California ground squirrels, fox squirrels and grey foxes; many other mammals including mountain lions are present. It is a chief remaining refuge for the threatened Alameda whipsnake, California red-legged frog. Less common wildlife species include the reintroduced peregrine falcon, ringtail cats, and to the east American badgers, San Joaquin kit fox, roadrunners, California tiger salamander, and burrowing owls. There are also exotic (non-native) animals such as the red fox and opossum, the latter being North America's only marsupial.

In September and October male tarantula spiders can be seen (Aphonopelma iodius) as they seek a mate. These spiders are harmless unless severely provoked, and their bite is only as bad as a bee sting. More dangerous are black widow spiders, far less likely to be encountered in the open.

In the wintertime, between November and February, bald eagles and golden eagles are present. These birds are less easily seen than many raptors; golden eagles, particularly, fly at high elevations. Mount Diablo is part of the Altamont Area/Diablo Range, which enjoys the largest concentration of golden eagles anywhere. In recent years there have been credible sightings of California condors, which have been reintroduced at Pinnacles National Park, located to the south in the Gilroy-Hollister area.

Of special note as potential hazards are Northern Pacific rattlesnake. While generally shy and non-threatening, one should be observant and cautious of where one steps to avoid accidentally disturbing one. They are often found warming themselves in the open (as on trails and ledges) on cool, sunny days. Other wildlife to avoid include fleas, ticks and mosquitoes. There has also been an increase in the mountain lion population in the larger region and one should know how to respond if these animals are encountered. Please see the mountain lion safety tips in the mountain lion article.

반응형

'1. Dr. Sam Lee > 여행스케치' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 169. UTAH STATE IN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (0) | 2023.06.16 |

|---|---|

| 168. Coastal to Hill 88 no Tennessee, Mill Valley, CA (0) | 2023.06.07 |

| 166. Bean Hollow State Beach, Pescadero, CA (0) | 2023.06.01 |

| 165. 05/14/2023 Mother's Day & 05/20/2023 Gathering party before the Alaska Mushroom hunting trip (0) | 2023.05.21 |

| 164. Los Trancos Trail to Fern Loop Trail, Palo Alto, CA (1) | 2023.05.14 |